Some of us are called to the ocean. In Maine we know there is a siren song that pulls many away from the land into a life of lobstering. Children of lobstering dynasties are out hauling before they turn double digits, and some even captain their own boats while in their teens. Generations of families here rely on lobstering to make a living. It’s in the blood and ethos of these salt-stained peninsulas.

The lure of lobstering is freedom, independence, and big money. One can earn a lot more hauling pots than in a typical first job in fast food or retail. So how do we encourage students who love the sea to stay in school long enough to earn a diploma and possibly consider higher education? Some are fortunate to have access to excellent programs that allow them to work and study at the same time.

Young people who love to work with their hands have difficulty sitting still in a classroom for the duration of a typical lesson. Their style of learning is more kinetic; they want hands-on activities and opportunities to learn through doing. A few dedicated educators have been at work on the problem of keeping these kids in school because, for all their abilities and weather-worn appearance, they are minors, children who still need adult guidance. It’s hard to think about the future when the present moment is filled with sunshine, seagulls, and a pocket stuffed with cash.

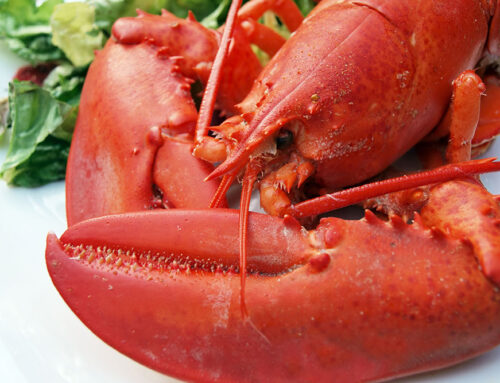

The Fisherman’s Academy at Oceanside High School in Rockland (the lobster capital of the world and home of the Maine Lobster Festival) serves this population of would-be high school dropouts and meets them where they live. The program does not try to squeeze these students into an educational model that doesn’t suit their needs and abilities. It educates future lobstermen and -women in skills they can actually use.

A course in using hand tools, for example, was particularly helpful to one participant, who expressed excitement to learn something in school that would benefit her while out hauling. In other courses, students are tasked with projects like creating an online lobstering dictionary. Some spend a week studying and working at The Apprenticeshop, a boatbuilding school in Rockland. These experiences are meaningful to these students and change the way they feel about their place in school.

The Rockland curriculum, developed in 2015 by then-principal Renee Thompson, is modeled after something pretty progressive happening at Deer-Isle Stonington High School, a place once known for truancy and bad behavior. Now there is a strong group of young lobsterman learning through traditional strategies about the subject that interests them most. In English class they read books like Sebastian Junger’s nonfiction cautionary tale The Perfect Storm or a classic like Moby Dick. In a navigation course students learn about trigonometry and geometry. These young people learn to be their own advocates; by giving them the tools and language to affect change upon the politics that govern their lives, we are raising more conscientious, empowered citizens.

These unique programs are helping the students and communities of Maine in ways that have yet to be measured. What we can see immediately is that these once sullen, often absent teens are collaborating, commiserating, and staying in school. They are the foundation of our economy; without these young men and women, we would have no lobster, and no Maine Lobster Festival. We owe them our respect, support, and understanding. They are the future of us.