Brian Baker, a sternman who works out of Cushing, Maine, often takes photos while he’s working. His hobby, turned into a Facebook page called “Salt Baked Photography,” aims to give the public a glimpse into the beauty of his natural surroundings. He and his fellow Maine lobstermen continuously try to spread awareness of what good stewards they are of the industry.

Baker started lobstering 12 years ago. “I went to college for computer science and graduated, but things didn’t work out,” he said. “My uncle, who is a lobsterman in Cushing, invited me to be his sternman, so I started working for him. That first summer I’d just take pictures from my phone and post them on my personal Facebook page. Based on the response I got from that, I decided to share more photos and make a business Facebook page with a wider audience. Not everyone gets to see the sunrise and the views we see on a daily basis.”

He compares lobstering to farming when explaining how lobstermen regard the health and safety of their catch.

“We feed these lobsters throughout their entire lives with our baited traps,” Baker said. “We grow them to a certain size until we can harvest them. If they’re undersized, we throw them back, which allows them to grow and promotes the sustainability. But, if they’re oversized, we also throw them back so they can mate with other larger lobsters. So for example, if we are V-notching female lobsters and letting them go, it only makes sense to let the larger males go as well, so they can reproduce. There’s a logic and science to that as well.”

The V-notch program was created by a fisherman to mark the tail flipper of egg-bearing females as healthy breeders so lobstermen will throw them back. “It takes several sheds for the mark to grow back in, ensuring many years of reproduction,” Baker said. “So, even if she is of legal size and isn’t carrying any eggs at the time, she is let go if her tail is notched.”

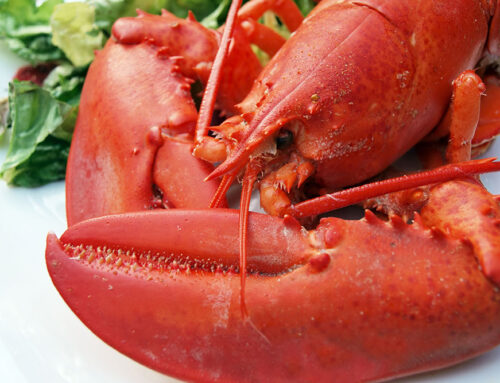

To measure each lobster, a lobsterman uses a brass gauge and measures from the eye socket of the lobster to the back of the main carapace (or body shell), aiming to keep only the lobsters that are within legal measurement. Anything under 3.25 inches or over 5 inches gets tossed back into the sea. Baker noted that it takes approximately seven years for a lobster to grow to be 3.25 inches.

“We do this because we look ahead to the next generation,” Baker said. “We want the next generations to have the same lifestyle as we have, and that’s why we’re always looking to the future.”

On the coast of Maine, the lobstering season is year-round, but most lobstermen stay “up inside” the state waters and go to haul in the summer, fall, and early winter because that’s when the season is viable.

Others, like Baker’s crew, keep traps further offshore, which allows them to harvest lobster all year. “From June until about Christmastime, most lobstermen are out fishing, but lobsters move farther offshore during the colder weather,” he said.

Each Maine lobsterman holds a commercial license that allows him or her to fish 800 traps. “There are different zones, but there’s also an understanding — that’s not technically law — among all lobstermen, where if you live in one town, you don’t fish in the waters of another town,” Baker said.

In coordination with Maine Lobstering Association and Department of Marine Resources, the limits and restrictions are determined according to how many licenses have been issued and various other factors.

Baker said inflation and gas prices have deeply impacted working conditions for lobstermen this summer, but the biggest ongoing challenge comes from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s efforts to protect the North Atlantic right whale.

“NOAA’s argument is Maine lobstermens’ gear is responsible for right whale deaths, but the science just doesn’t back any of that,” he said. “So, we’re forced to do all of these modifications to our gear that’s costing Maine fishermen all kinds of money and time.”

Baker said those modifications, such as requiring thinner ropes and putting more traps on a line, also create a more dangerous working environment. “That makes it more likely for us to get hurt or pulled overboard,” he said. “We’re willing to work on a middle ground based on scientific fact, because we obviously care about the whales; we care about every part of the ocean.”

For all of the daily challenges and hard work, lobstering isn’t just a job, it’s a lifestyle. “It’s definitely not where I thought my life path would take me,” Baker said, “but I couldn’t be happier.”

Stay tuned to our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter social media platforms to see a wrap-up of the best of the Maine Lobster festival this year. Find out more at https://mainelobsterfestival.com.